Alport Syndrome Foundation Seeks Therapies for Hearing as Well as Kidney Loss

WASHINGTON — Alport syndrome, a rare genetic disorder that leads to life-threatening kidney damage, also causes hearing loss — yet that part of the disease is poorly understood and receives relatively little attention.

Gina Parziale, executive director of the Alport Syndrome Foundation, hopes to change that.

“We want to hear from patients about how important quality-of-life issues are,” she said. “Very little research is being done on hearing loss in Alport. We want to better understand if people are satisfied with wearing hearing aids, or if they’d appreciate an interventional therapy — and how important that is to them compared to kidney disease.”

Parziale became the foundation’s first full-time employee in February 2016. Until then, the Phoenix-based nonprofit, which was founded in 2007, had always been staffed by volunteers.

Alport Syndrome News spoke with Parziale at the Rare Diseases & Orphan Products Breakthrough Summit last month. The National Organization for Rare Disorders sponsors the annual event in Washington.

Parziale said roughly 30,000 Americans have Alport. Until two years ago there was no way to obtain a good count on patients. That was when Alport was added to the World Health Organization’s list of ICD-10 medical codes. Healthcare providers, insurers and others use the coding system in their work.

“We’ve only recently been able to track” the Alport rate, Parziale said. Alport accounts for 3 percent of U.S. children with chronic kidney disease and 0.2 percent of adults with an end-stage renal disease, the foundation says.

Alport affects men, women differently

The Alport Syndrome Foundation connects about 8,000 members of the Alport community. Its has about 1,000 patients in its private, closed Facebook page.

It works with like-minded groups around the world, and in September organized an international workshop on Alport in Glasgow, Scotland, in association with the European Society for Pediatric Nephrology.

“Our mission is to provide education, awareness, research and advocacy for those who have Alport syndrome,” Parziale said. “Alport is a genetic condition that causes kidney failure and hearing loss, and so we focus our efforts on stimulating research into potential therapies and better understanding the disease.”

Without treatment, X-linked Alport syndrome, the disorder’s most common form, leads to kidney failure in half of men by age 25, and in 90 percent of men by age 40.

“With ACE inhibitors, men are able to go into their later 20s or early 30s without needing dialysis, but it’s still inevitable,” Parziale said. In addition, 80 percent of men with Alport lose their hearing — often while they’re still teenagers. The full name for an ACE inhibitor, which is widely used to combat high blood pressure and heart problems, is angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor.

X-linked Alport syndrome progresses far more slowly in women, Parziale said.

“Many women were told for years that they had benign hematuria, or blood in the urine, and not to worry about it,” she said. “When life expectancy was in the 50s and 60s, we didn’t realize it affected women. But then people started living longer, and now we’re seeing women in their 60s starting to develop kidney problems, and they do need to worry about it.”

Hearing loss a crucial quality-of-life issue

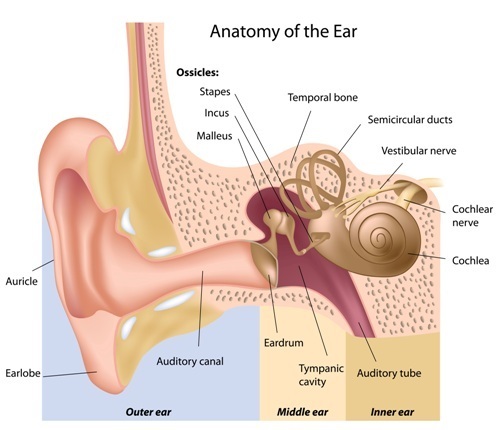

At the same time, about 70 percent of Alport patients suffer hearing loss due to the genetic mutation that affects the type IV collagen family of proteins. Type IV collagen is a key part of structures called basement membranes that are present in all tissues, including the kidney, inner ear and eye. Faulty versions of the protein are associated with Alport.

Although scientists are aware of the genetic connection, “we don’t actually understand what causes hearing loss, so there are no therapeutic targets or mechanisms that would help,” Parziale said. “While certainly kidney failure is a more impactful condition, hearing loss is also a very large quality-of-life issue. And as we search for a cure, we don’t want to minimize the quality of life.”

Put another way, she said, “this disease in particular affects both hearing and kidneys. There are people who feel very strongly that all the research should go to kidneys, because you don’t die from hearing loss.”

Alport patients can wear a hearing aid, of course, but that solution might not be ideal for everyone. But therapies to prevent hearing loss could have side effects.

“We want to understand if people would accept a therapy if it did have potential side effects, and what effects they might be,” Parziale said. “If a pill or therapy allowed you to keep your hearing, would you accept any potentially negative side effects?”

Annual campaign aims to raise $175,000

Parziale, who lives in New York, has spent the past 18 years as a rare disease fundraiser. She began at the Muscular Dystrophy Association, where she spent six years, then raised funds for the American Liver Foundation for another six years. Before coming to the Alport Syndrome Foundation, Parziale wasexecutive director of its New York/Northeast chapter of the Pulmonary Hypertension Association.

The foundation’s biggest event is its annual campaign, which runs from September through December — so it’s currently in full swing. This year’s goal is $175,000, up from the 2016 goal of $150,000. The group also holds an annual Arizona 5K for Healthy Kidneys run.

To prevent any perceptions of conflict of interest, the foundation prohibits its board members from testifying at regulatory hearings of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Parziale said.

“But if a pharmaceutical company wants to send us to their headquarters, we are certainly willing to do that,” she said. “We have a clear-cut policy: here’s what we do, and here’s what we don’t do. It makes the conversation with industry easier.”

She added: “The FDA may say, ‘Of course you’re supporting this drug — they’re giving you $100,000.’ For this reason we do not accept money for clinical trials, and we don’t accept money to provide information. It keeps things cleaner.”

Regulus, Reata therapies are in clinical trials

The Alport Syndrome Foundation has a 2017 budget of about $600,000, with industry grants covering $150,000. The largest corporate donors are San Diego-based Regulus Therapeutics and Dallas-based Reata Pharmaceuticals, both of which are working on Alport therapies.

Regulus is testing RG-012 in a Phase 2 clinical trial that involves 40 Alport patients. RG-012 inhibits a microRNA called miR-21 that researchers believe contributes to kidney scarring and tissue damage. MicroRNA regulates genes that produce collagen protein, faulty versions of which are associated with the disease.

The HERA trial (NCT02855268) is likely to conclude in late 2018, Regulus said.

Meanwhile, a Phase 2 trial showed that Reata’s bardoxolone methyl helped nine out of 10 patients with chronic kidney disease stemming from Alport.

After 12 weeks of treatment, 90 percent of the 30 patients had “demonstrated clear improvements in renal function,” Dr. Colin Meyer, Reata’s chief medical officer, said in a press release. That allowed researchers to launch Phase 3 of their Phase 2/3 CARDINAL trial (NCT03019185) in July. It will have 150 participants and last for two years.

“The drugs being tested have received orphan drug status, so we are eager to support anything that moves forward,” Parziale said. “We support the Orphan Drug Act, and we advocate for Alport patients to have affordable access to treatment. We aren’t a political organization, but we feel it is imperative that we provide policymakers with the expertise we have in terms of what would benefit or harm our patients.”

Orphan drug status is aimed at accelerating treatment development and regulatory approval.

Dialysis costs around $85,000 a year — one reason that Alport patients would welcome anything that can delay or eliminate it, Parziale said.

“Right now, Alport patients go on ACE inhibitors, and then dialysis and transplants,” she said. “If these [Regulus and Reata] drugs are approved, they’d most likely cost less than the current costs of dialysis and transplant.

“After a transplant, they can have great lives, but they’re always taking immunosuppresants, which have risks of their own,” she said. “Obviously, while we appreciate that dialysis saves many lives, it’s not our end goal. Our goal is to prevent the need for dialysis and transplantation.”

Jan

I reagularly scour the internet searching for hearing loss clinical trials only to find that usually people with genetic reasons for hearing loss are excluded. My son was transplanted 5 years ago and I see how his hearing loss affects his life. I agree that some trials should focus on this facet of the disease, as it is a big deal for those affected.

Patrick Wise

My son is 8 now and has had hearing aids since 5 years old. He was diagnosed with AS at 22 months old by kidney biopsy. I would like to know more about any treatment that might help hearing loss so our son can read and comprehend better. This may open more doors for his future than those that may close. It would depend on the side effect profile.